Published: December 31, 2023 | 1 min read

The #1 Risk Factor For Calcium Oxalate Kidney Stones

ARTICLE SHORTCUTS

- WHAT IS OXALATE?

- HYPEROXALURIA AND THE RISK OF KIDNEY STONES

- CAUSES OF HIGH URINARY OXALATES

- SIMPLE TIPS TO PREVENT HYPEROXALURIA

If you are frustrated about your recurring calcium-oxalate kidney stones, you have come to the right blog! This article will discuss how to beat the #1 promoter of kidney stones – OXALATE.

Excessive urinary oxalate (a.k.a. hyperoxaluria) is a nightmare for anyone who forms kidney stones. Too many oxalates can wreak havoc all over our bodies in addition to being the root of calcium oxalate kidney stones. But, how much oxalate is too much?

Before we dive into this, let’s first get an understanding of what we’re working with.

WHAT IS OXALATE?

Oxalate is an organic acid produced by plants as a part of their biochemistry. It is also called a “plant-defense chemical” as it is designed to keep humans, animals, and insects from munching on them. In short, it’s not nutritious.

In fact, oxalates can be downright dangerous to our human biochemistry. Oxalate is not used in our bodily processes and can buildup in various tissues and organs in the body (a.k.a. systemic oxalosis). That said, it has been linked to the following disorders:

- kidney damage due to recurrent stones

- thyroid disease

- cardiovascular diseases like heart failure and myocardial fibrosis (scarring of heart’s tissues)

- skin rashes

- bone disease

Another reason why plants produce oxalates is to bind the calcium absorbed by the roots. So, a plant’s oxalate load depends on the calcium content of the groundwater. This means oxalate levels may vary even for the same plant variety.

Now, how does this relate to kidney stones

HYPEROXALURIA AND THE RISK OF KIDNEY STONES

FACT: the #1 promoter of kidney stones is OXALATE.

Calcium-oxalate stones comprise about 80% of global kidney stone cases. Worse, the recurrence rate is about 60% in 10 years.

Among all the substances in our urine, oxalate is the strongest promoter of kidney stones. High levels of urinary oxalate are defined as exceeding 25mg/day of excretion. However, when urinary oxalate increases to 40 mg/day, the risk for kidney stones increases by 2.5 to 3.5 times. Meaning even small changes in urinary oxalate can be risky.

Suppose you love spinach. Did you know that a cup (50–100 g) of your favorite contains around ~500–1,000 mg of oxalates? And who eats just one cup? Sadly, most vegetables we eat are rich in oxalates.

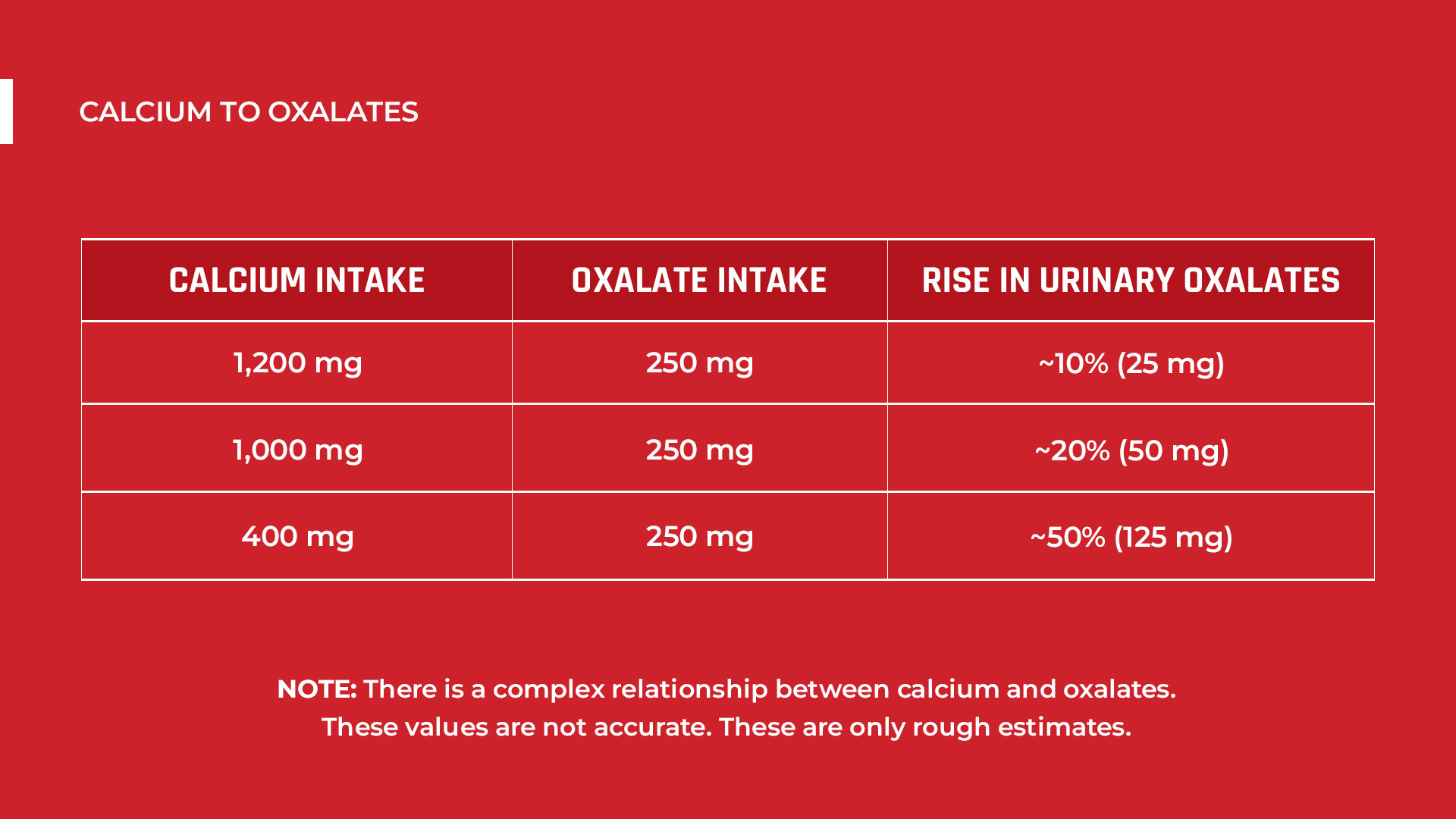

According to the research, urinary oxalate (in a 24-hour urine culture) increases by roughly 2.7mg for every 100 mg of dietary oxalate. That’s when calcium intake is 1000 mg per 50–750 mg oxalates.

But what if calcium intake is low?

Brillant question! If you aren’t consuming the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of calcium (which is 1,200mg), you’ll be at greater risk of kidney stones. That’s because 15–25 mmol (600-1000 mg/L) of calcium binds with 1–3 mmol (88-264 mg/L) of oxalates. Meaning, oxalates require large amounts of calcium.

So, if you take about 250 mg of oxalates with just 400 mg of calcium, your urinary oxalate will increase by more than 50%. This is why many people form kidney stones.

CAUSES OF HIGH URINARY OXALATES

If you think DIET is the leading cause, you are right.

But for your peace of mind, we have listed below all the possible causes of high oxalate levels in the urine:

1. Bad Dietary Practices Rich In Oxalates

For most of the population, hyperoxaluria is a result of inappropriate dietary choices. Vegan/Vegetarian diets and the “Standard American/Western” diet are among the greatest culprits for this.

Gut absorption from dietary sources produces almost all of the oxalates in our blood and urine. But researchers have contradicting opinions about this.

For instance, one research said that dietary oxalates may be responsible for up to >50% of total urinary oxalate excretion. But most researches claim that only 10 to 20% are from the diet. To be honest, both these claims are unreliable. That’s because there aren’t many studies focusing on diet’s real impact on oxalate excretion even at present.

Proteins from the solute carrier (SLC26A6) family absorb oxalates in the gut and the colon. Solute carriers are responsible for carrying different substances throughout the body. That includes oxalate transport. The bacteria Oxalobacter formigenes that feed on oxalates play an essential role in this process. As these bacteria degrade oxalates, the amounts available for absorption is reduced.

Oxalobacter formigenes are naturally occurring bacteria in the gut. But they can be absent, less or abundant in some people. Diet and antibiotics use are the main reasons. People who eat a high-fiber diet will most likely have abundant Oxalobacter formigenes. These bacteria use fiber to thrive. The truth is, the human body does not possess enzymes capable of metabolizing oxalate. That’s why the presence of these degrading bacteria are helpful. It further proves that oxalates are not designed for food.

2. Excess Vitamin C

Some oxalates are also converted from excess vitamin C. The enzyme glycolate oxidase aids this minor process in the liver, while L-gulonolactone oxidase aids this process in the kidneys. Nevertheless, dietary intake of as much as 250-500 mg may not pose stone risk. But there is evidences that vitamin C intake of around 700 mg to over 1000 mg daily, especially from supplements, is a risk factor for hyperoxaluria.

NOTE: This is telling us something! Humans did not evolve to consume high amounts of plant matter. If we did, we would not encounter issues with Vitamin C converting to oxalate in cases of excess.

3. Glycolate Metabolism

Glycolate metabolism in the liver gives off some oxalates too. In this process, the enzyme glycolate oxidase converts an acid called glycolate to another acid, glyoxylate. Then, glyoxylate will be further converted to oxalate. These acids are not directly sourced in foods. Instead, they are products of amino acid conversions in the body.

Actually, many researches claim that 40 to 50% of oxalates are derived from glycolate metabolism in the liver. Others would back it up with claims that vitamin C adds the other 40 to 50%, and only the remaining 10 to 20% are from the diet. But mind you, none of these numbers are based on accurate quantitative techniques. Oxalates are mostly byproducts of what we eat.

4. Heredity

Also, there are rare cases of a condition called primary hyperoxaluria. This results from a genetic defect that increases the enzymes responsible for converting glyoxylate to oxalates in the liver. Fortunately, primary hyperoxaluria is extremely rare; affecting around a mere 3 out of 1,000,000 people. The symptoms will usually appear in the toddler years. These symptoms include:

- Recurrent kidney stones

- Frequent wetting of bed

- Having a hard time controlling urination

SIMPLE TIPS TO PREVENT HYPEROXALURIA

The best route to lower your urinary oxalate levels is through dietary changes. This is the best advice we can give you!

Maintaining a 24-hour urinary oxalate level of 25mg (or less) is best. That means urinary oxalate should be around ≤20 mg oxalate/L urine. A 24-hour urine test is recommended every three months to track your oxalate levels. This will help you gauge the impact of your dietary changes.

Many foods we consume are high in oxalates. These include potatoes, spinach, almonds, corn, and nuts. Actually, most vegetables are high in oxalates. It’s time to kick all these out of your diet.

You can attempt to lower your oxalate intake to less than 80mg per day. But, this is often difficult to manage as oxalate is cumulative (builds up in your system) and has a way of sneaking back into your diet if you’re not very structured with your plan.

Since it can be difficult to reshape your diet on your own, getting a guide is necessary for you to succeed. Work with someone who’s been there and accomplished what you want to accomplish with regard to your kidney stones. Why reinvent the wheel?

Here are a few resources to help you stop kidney stones and get your life back:

- Diet’s Impact on Kidney Stones Blog

- Kidney Stone Diet Prevention Course Inside the Stone Relief Community

- One-On-One Diet Coaching

References

- Hyperoxaluria

- Dietary oxalate and kidney stone formation

- Contribution of dietary oxalate to urinary oxalate excretion

- Contribution of Dietary Oxalate and Oxalate Precursors to Urinary Oxalate Excretion

- The Induction of Oxalate Metabolism In Vivo Is More Effective with Functional Microbial Communities than with Functional Microbial Species

- Total, Dietary, and Supplemental Vitamin C Intake and Risk of Incident Kidney Stones

- Primary and secondary hyperoxaluria: Understanding the enigma

- The effect of pH on the risk of calcium oxalate crystallization in urine

Comments or questions?

Responses